3 Reasons Logo Design Clients Suck (And How to Respond)

Logo design has to be one of the trickiest pieces of design work when it comes to dealing with clients. It seems almost inevitable that what you imagine will be a quick and easy job turns into a nightmare of never-ending reworks.

Today we’re going to discuss what types of problems typically arise in logo design and how you can prepare for them.

Another Rant

Every now and then I warn you that an article is not merely informative but also a bit of a personal rant. This is one of those articles. I was chatting with a friend the other day about a logo project that he was working on that had simply gotten out of control. The story struck a chord with me because I’ve encountered the same exact problems with logo clients in the past. In fact, I think most designers that have taken on logo projects have faced similar issues.

The following uses a healthy bit of hyperbole but I think it hits home with real struggles that designers encounter from logo clients. Hopefully the recommendations will help you avoid disaster before it strikes.

It is not my intent to paint the client too harshly. These are the people that pay the bills and I’m a huge advocate of stellar customer service. However, I think that logo clients are uniquely prone to take advantage of the generosity of designers, even without knowing it, and I want to be sure that you prepare yourself well enough so that this doesn’t happen.

The Client Wants to Be the Designer

Most of the time, non-logo clients will have a general idea of what they want or will at least offer some suggestions for the overall look they want you to shoot for. This is often quite helpful as it gets your brain working in a direction that is hopefully in line with the client’s interests.

The nice thing is that, for the most part, clients with big projects are intimidated by the design aspect. They know that designing a website is a big, important task and they don’t really know where to start, which is why they hire you. They trust your expertise and often allow you to come up with some solid concepts on your own to kick off discussions.

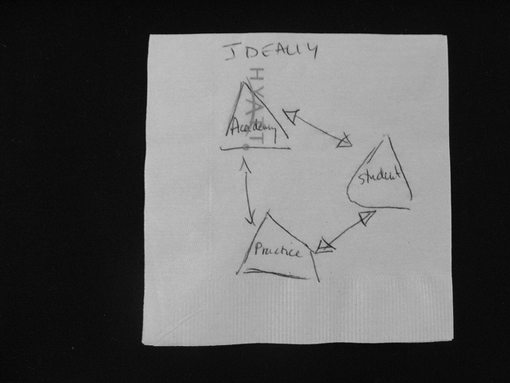

With logo design clients, the task at hand is much less intimidating. Consequently, you frequently end up with someone who already has a fairly solid idea of what they want, which sounds great, but leads to you simply converting a horrible sketch on a cocktail napkin to a horrible vector logo. It’s a rare non-designer that comes up with an awesome logo.

How to Respond

If this happens to you, don’t feel bad for thinking “easy money” and going with it. In fact, that’s the high road. This is especially the case if you’re running short on work! When you need cash, almost every client is a good one.

For me though, I enjoy actual design work and have the freedom to be fairly selective about the projects that I take on. Consequently, I’m much more inclined to take on a real logo design project where I get to, you know, design a logo. If a client already has their logo worked out and just needs someone to draw it in Illustrator, they don’t need me, they need a cheaper version of me and honestly, I don’t mind telling them so. You’ll be hard-pressed to find someone who gets angry with you for saving them money.

Obviously, the choices here are clear. If you need the work, take it. Hand over the ugly logo that the client wants and whistle on your way to the bank (and maybe skip the upload to your portfolio site). If you don’t want a simple vector-conversion job though, kindly explain to your client the nature of the service that you offer. Maybe you’ll convince the person to let you design a professional quality logo for them, maybe not. There are other fish in the sea.

It Seems Like It’s Easy to Start Over

With a website or other design, the overall product is complicated enough that a moderately sane client can usually find at least a few things that they like about your initial concepts. The direction can then proceed with tweaks and changes that leverage the work that you’ve already done.

With logos, the final product feels insignificant by comparison. If a client doesn’t like the three logos that you presented the first time, you’re likely to be sent back to the drawing board. Before you know it, you’ve spent eighteen hours coming up with twelve finished concepts and your client is still emailing you sketches from neighbors, family friends and anyone else that they know who has an idea and a pen.

How to Respond

The problem here is obvious. Logos seem fun at first but they tend to turn into those projects from hell that simply won’t go away. In the hands of a designer unexperienced with the business side of freelancing, these projects can quickly become more trouble than they are worth and leave you swearing to the gods of the pen tool that you’ll never take another logo job again.

Keeping logo projects under control requires up front planning and decisiveness. From the start you absolutely must spell out a clear price for the work that you intend to do. Your first reaction might be to simply throw a price on a logo design: Logo Design – $X, this is where you get into trouble though because your agreement is so vague that you end up working until the client runs out of great new ideas.

Instead, you need to be more specific: $X for three unique concepts and $X for every additional concept requested by the client. This structure makes it clear that you are charging a set amount for three distinct ideas, if a client wants you to go back to the drawing board after that, fine, but the bill will be higher as a result.

Never Ending Edits

Once you finally get the general concept nailed down, the same story arises with the tweaks. The client will want to see a version in blue instead of red, with a square instead of a circle and with a different font. On top of explicit suggestions like that will be vague direction such as, “make it edgier” or “I want it to pop more”.

Though you’re not completely starting over this time, the rounds and rounds of edits still add up and eat away at any profit that you had hoped to make. Remember that your time is worth a certain dollar amount and that when the time you spend on a project equates to more than you’re earning from it, you’re losing money. Opportunity cost is very real in freelance design and should be taken seriously.

How to Respond

Again the proper response is to be as specific as possible up front. In the previous section we refined our generic pricing structure from simply $X for a logo design to $X for three unique concepts. Let’s make this even more specific so that your clients know exactly what they are getting.

- Three unique logo concepts

- Two rounds of minor changes or tweaks to the selected concept (color, font, etc.)

- $X for each additional unique concept request

- $X for each additional round of changes

Notice that what we’ve done here is make it crystal clear what your logo design fee covers and what it doesn’t. This is infinitely better than a vague agreement that gets the client a designer to abuse for a set amount. This may seem like overkill or even an unnecessarily rigid way to price logos, but it’s not, it’s just good business.

Conclusion

To sum up, logo design clients suck because they often don’t really need or want a designer. When they do, they will frequently begin a seemingly ceaseless cycle of both major and minor concept changes that will suck any benefits you might receive right out of the project.

To battle this, make sure that you’re clear about what types of projects you do and don’t want to take on. Also, one of the most important things you can do is set up a solid and well-defined pricing structure that allows the client to see how much work you intend to put into the job and how much additional cost will be associated with extra tasks.