How Dogs and Rats Can Make You a Better Designer

Today we’re going to venture far outside of the designer’s typical learning bubble. We’ll leave Photoshop behind and pick up the tools of a marketing executive studying consumer behavior.

This article will teach you two distinct approaches to impacting your target audience. Knowing these terms and theories will not only help you become a more effective designer, they’ll also make you look super smart at work!

You’re a Marketer!

As a designer, you’re a marketer whether you like it or not. Some design jobs might be more obviously connected to marketing than others, but we’re all in the same game in the end. I used to design advertising inserts for newspapers, this was obvious marketing and doesn’t take any stretch of the imagination to see it. But what about web designers? Throwing some photos and text on a homepage isn’t really marketing right? To answer this question, I grabbed a website at random from a gallery, here’s what I came up with:

The designer in me says that this is a good looking page. The volume of space has been structured nicely around the objects, the alignment is strong and the visuals are attractive. End of story right? Wrong.

Everything on this page is meant to sell me on the product being promoted. Obviously, there is the messaging, but let’s assume that the designer had nothing to do with that. There’s still the large shot of an iPhone so I immediately know that we’re talking about an app, the inclusion of a hand, which gives a personal human element, and the crowd in the background, which is a subtle suggestion that the product is fun and exciting.

Even basic design elements like colors and fonts are all structured communication that affect the viewer in a hopefully positive enough way that they are encouraged to try the product.

You can see these same tactics in place on freelancer portfolios, online games, social networks and any other professionally designed website. The question I like to ask is, “If design is a key element of any marketing campaign, why aren’t designers taught more about the basic principles of marketing?”

How We Learn Affects How We Shop

Today’s topic is conditioning. Loosely defined, this refers to how we learn something. On the surface, theories about learning might seem nearly useless to designers, but when you dig deeper you’ll see that some incredibly valuable insight can be gained.

Every piece of marketing and advertising we see is ultimately aimed at teaching us something (see mom, television is educational!). A soda commercial wants to teach you that Pepsi tastes delicious, a church billboard wants you to know that God exists and an Abercrombie t-shirt is meant to help you learn where all the cool kids shop.

It’s all a grand scheme to condition you to think a certain way. Effective marketers understand this and educate themselves on learning techniques so that they can make stronger, more effective appeals to their potential customers. Likewise, if you as a designer pick up these techniques, your visual appeals can become more effective.

Classical Conditioning: Pavlov’s Dogs

There are two basic types of conditioning, classical conditioning and operant conditioning. Both are helpful for designers so we’ll briefly explain them each and discuss how you can apply them.

We’ll start with the older of the two theories: Classical Conditioning. Classical conditioning theory rose out of experiments performed by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in the late 1800s.

We all know the story well from high school. This lucky guy devoted his time to collecting and measuring the saliva excreted by canines (and occasionally children, but child experimentation is frowned upon these days). Good old Ivan noticed that his dogs would salivate as a result of seeing and/or smelling delicious “meat powder.”

Further observation revealed that the dogs developed this same response to simply seeing the person who normally fed them, revealing that this wasn’t merely a physical reaction to a scent but something that was set off psychologically.

Pavlov posited that he could manipulate this tendency and create a “conditioned” salivation response through the use of a typically neutral stimuli. Though he likely also used electric shocks and other not-so-animal-friendly techniques, the most famous (and nicest) stimuli was a bell.

By ringing a bell every time he fed the dogs, Pavlov eventually taught the dogs to salivate purely upon hearing the bell. We call the meat powder an “unconditioned stimulus” (causes a natural reaction) and the bell a “conditioned stimulus” (causes a learned reaction).

So What?

Enough with the dog spit, what does this have to do with being a better designer? As you design a website, an advertisement, a brand, etc. think about exactly what it is you want to teach the viewer to think about the product or service you’re promoting.

Marketing agencies do this in droves. As an example, there is one particular “unconditioned stimulus” that always gets a reaction: sex. We can instantly think of a number of brands that leverage this, the most controversial and desirable stimulus on the planet. Here’s one that immediately comes to mind:

Every single Axe advertisement I’ve ever seen leverages the power of sex. In this case, the 15-25 year old males that the campaigns are targeted towards are the dogs (a fitting metaphor) salivating over attractive women and the promise of sex. The ads depict something sexual (unconditioned stimulus) and immediately catch your attention (unconditioned response).

Meanwhile, they claim that their product (conditioned stimulus) is the thing driving all of this sexual energy, thus making young men run out and buy this stuff and spray it all over themselves until every nasal cavity in a three mile radius is ruined (conditioned response). The result is a successful and powerful brand image that makes its owners lots and lots of money.

Operant Conditioning: Skinner’s Rats

Operant conditioning, also known as instrumental conditioning, takes a related but different approach. Here the learning model is based on rewards and punishment.

Yet again we turn to an old guy doing weird experiments with animals. B.F. Skinner was a behavioral psychologist who built some interesting boxes in the 1930s called “operant conditioning chambers”. In these chambers, rats, birds and other creatures (in case you’re wondering, Skinner used kids sometimes too) took part in widely varied experiments that centered around positive and negative reinforcement. A basic example is teaching a rat that when he presses a lever, he receives a piece of food. The rat soon begins to associate the pressing of the lever with something positive.

When we apply the results of this experiment, an obvious model of behavior results. Bob does something, Bob gets a reward, Bob does something again.

Other interesting variations were also observed. Even when Bob is trained to expect something positive from an action, if something bad happens as a result of the action (punishment), Bob will quickly learn to avoid that action (if Axe body spray makes the ladies hold their noses, Bob won’t buy it any more).

One of the more interesting findings is that the time between the action and the reward directly relates to the strength of the connection that the subject forms between the two. If the rat presses a lever and then receives a piece of food thirty seconds later, the lesson is not as powerful as if the food had come immediately.

So What?

Operant Conditioning is a little trickier to apply to marketing. Obviously, punishment and negative reinforcement aren’t great places to start so you pretty much have to go with some sort of positive reward system.

The general concept is that the customer does something, such as purchase your product, and receives some reward as a result. The lesson that they learn is that purchasing your product yields positive benefits. Even if it was a one time thing, there has still been a positive emotional response that will cause the person to unconsciously associate positive feelings with their use or purchase of your product.

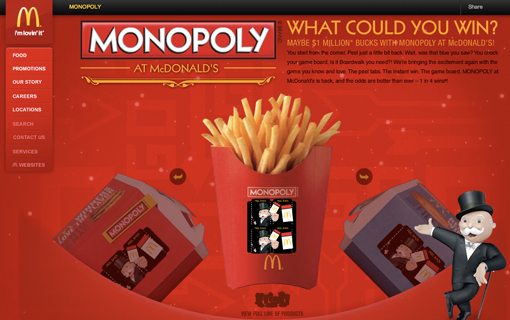

There’s one wildly successful use of this technique that comes to mind: the McDonald’s Monopoly game.

This ingenious scheme puts Monopoly pieces onto McDonald’s products. When you purchase a meal, you receive multiple game pieces that you can tear off and collect to win prizes.

Now, the key to this plan isn’t just the promise of a million bucks, some people either realize they have no hope for winning this or don’t want to take the time to search for and collect the necessary elements. Sure, plenty of people do just that but what about the rest? Why do they keep coming for more fries?

The answer lies in the instant winning. McDonald’s knows exactly how to keep you coming back: they place little instant win messages on one out of every 3-5 game pieces that reward you with a free order of fries, ice cream, breakfast or soda (pennies to them, pure bliss to you). Remember the rat and the lever, immediate feedback is stronger.

Applying this to Skinners experiments, you are the rat and McDonald’s is the box. When you purchase a Big Mac Meal, it’s like pressing the lever. As soon as you get the meal you tear off those game pieces and behold, you win something!

Like a rat who just got a piece of food you are quite excited about this event and will continue to buy Big Mac Meals (keep pressing that lever Mr. Rat) in the near future because of the positive connection you now have with doing so. Regardless of the fact that a free 99¢ ice cream cone doesn’t really justify paying $6 for a heart attack on a bun, you still gladly fork over the money.

Web Design Implications

Operant conditioning has major implications in the area of UX design. The web is a rich, interactive medium through which you can deliver a host of subtle rewards. It can be something as small as a beautifully animated hover effect on the “Buy Now” button or something as large as receiving some kind of free download for signing up for a service.

This expands to all kinds of areas. Any time your users do something that you want, reward them for it somehow. If someone tweets “Bob’s website is amazing”, offer them the courtesy of a ReTweet or a direct response. We’re all addicted to the notifications we get from social media and a ReTweet or @mention teaches your users to associate sharing your site with positive results.

An even strong motivator is money. Referral systems monetarily reward users for sharing links. If I tweet my Amazon referral link to a design book that I like and people subsequently click the link to purchase the book for themselves, Amazon gives me a portion of that sale as a reward for my actions. They get more sales, I get paid for something easy and B.F. Skinner smiles in his grave.

Isn’t This All a Bit Obvious?

Now, did you really need me to teach you that sex appeal and free stuff make for increased sales? Probably not. So what’s the point of learning all of the technical jargon?

An appropriate metaphor lies in the art of design. Think about the most important design principles that every good designer follows: contrast, repetition, proximity, alignment, etc. Now think about how simple these are.

Alignment: don’t just throw crap on the page, line it up. Proximity: if you think two things are related, they should probably go together visually.

Did you really need someone to teach you this stuff? Most of the principles of design are extremely intuitive and yet there are still bad designers. Studying these ideas takes this knowledge out of something you implicitly know and makes it something you explicitly understand and can therefore intentionally apply every time you create something. The result is better design.

Likewise, marketing principles are all fairly intuitive, but understanding them on a deeper level will give more purpose to your designs. Every time you approach a client’s website, logo, business card, etc., you should try giving a quick thought to conditioning. What is it that you are teaching the viewer with your current design? Now what is it that you really want to teach them? Dogs and rats my friends, dogs and rats.

Conclusion

I say it in almost every article I write, design is not just about making things pretty. By focusing purely on how to make Photoshop sing and dance, you’re leaving out at least half of the ultimate goal. No matter what you design for a living, you’re trying to convince someone of something. Whether it’s that a certain business is reputable or that a given web application is user friendly, understanding conditioning can go a long way towards ensuring your success.

Leave a comment below and let us know what you think of all this psychological mumbo jumbo. Do you think about conditioning when you approach a design project? Should you?

Title images by xiaofeng17 and bigfatrat.